You have to hand it to the likes of Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger, scientists who were instrumental in developing the field of quantum mechanics about 100 years ago.

They had their work cut out for them trying to explain to a sceptical public the forces that dictate how the world works on the atomic and subatomic scale.

Even Albert Einstein – whose own discoveries were towering reference points for these scientists – could never reconcile that quantum measurements and observations are fundamentally random.

“It is this view against which my instinct revolts,” he wrote in 1945.

We’ve learned much about quantum mechanics since then, including how the principles of superposition and entanglement explain how information can be processed in ways computers like our laptops and smartphones can’t match.

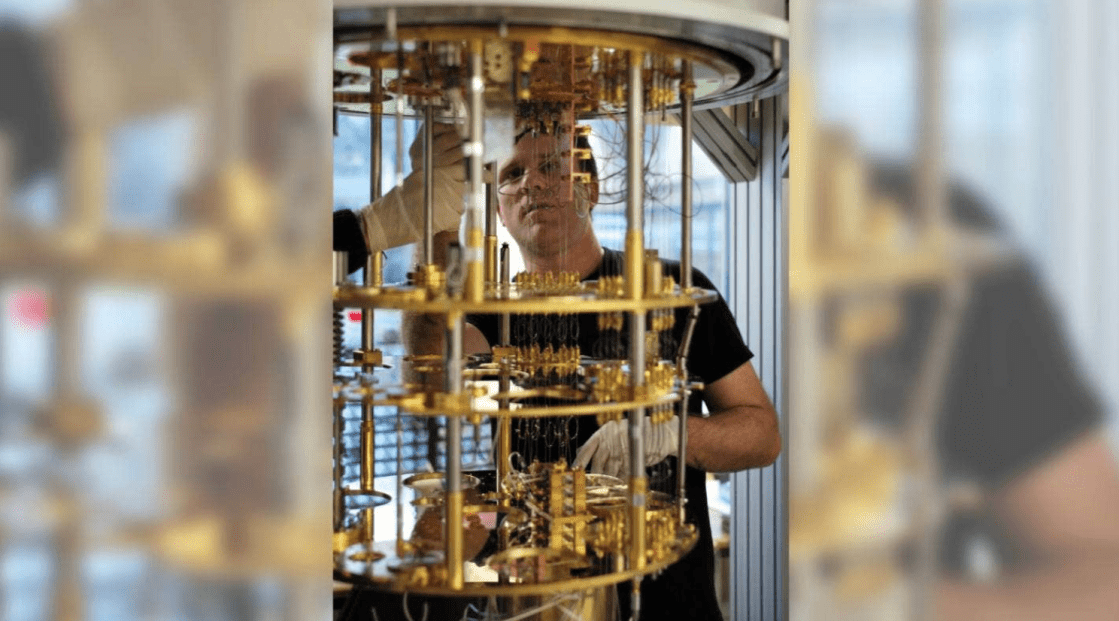

Last week I stood for the first time in front of a fully functioning quantum computer, IBM’s Quantum System One, at the company’s research labs in Yorktown Heights, New York.

The machine looks like a beautiful gold chandelier shrouded in a metal case that creates a vacuum in which the whole device is chilled to just above absolute zero, as cold as outer space.

The highly controlled conditions are required to eliminate interference that could prevent the quantum chip at the tip of the chandelier from doing its thing, which is to activate “qubits” – the quantum version of the “bits”, the digital ones and zeros our binary computers work with.

IBM, Google, Microsoft and numerous other companies and research institutions have demonstrated how quantum computers are very good at a narrow range of computational tasks, such as simulating nature. That’s already seen them put to work modelling molecules and in the complex field of materials science.

Programmers are now working on computer algorithms to expand the ways in which quantum computers can be used. Cryptography experts think large quantum computers could crack existing encryption systems, which would cause a cybersecurity nightmare.

But quantum computers will need to scale up massively in power and be less prone to errors to be useful more broadly. IBM last year produced Eagle, a 127-qubit processor for its quantum computer and plans to introduce Osprey, its 433-qubit chip this year.

Eventually machines with hundreds of thousands or millions of qubits could be available for number crunching on a scale we’ve never seen before.

It’s unlikely you’ll ever have a quantum computer on your desk or in your garage. Instead, IBM and its rivals rent access to their quantum computers as a cloud computing service.

Today’s regular computers aren’t heading for the dustbin either. They are better at a wide range of tasks and can work in tandem to make quantum computers more useful.

It’s unclear whether quantum computing can be properly applied to solving the big problems facing the world – new antibiotics or climate change.

But the blistering pace of technical progress suggests it’s a field heating up and one worth watching.

Originally published on Stuff.co.nz