In the mammoth task ahead of us to decarbonise the global economy so we can avoid the worst impacts of climate change, we’ve been warned against seeking ‘silver bullet’ solutions.

No fancy carbon-capturing technology is going to save us, only a fundamental shift to solar, wind and geothermal power and wholesale behaviour change that generates less hot air in our daily lives.

But government-funded labs around the world have indeed been quietly working on a silver bullet solution to the carbon problem for more than 50 years. Fusion power has mockingly been called the holy grail of energy that’s always 30 years away from being realised.

It’s a field shrouded in hype, misinformation and incredibly complex and difficult physics.

But yesterday came an announcement from the National Ignition Facility in Livermore, California, that is genuinely worth the hype. Scientists pointed 192 laser beams at a tiny fuel pellet in a nuclear fusion reactor and managed for the first time to produce slightly more energy than the lasers put in.

That’s what is known as ‘energy gain’ and is the key to unlocking a near-limitless, safe, carbon-free source of energy by replicating the forces at work in the solar system’s most productive energy generator, the sun.

It’s a different process to the nuclear fission that powers nuclear power plants and the tactical nukes Vladimir Putin currently has pointed at Ukraine.

Big like Higgs

It’s the biggest breakthrough in the world of physics since 2012 and the confirmation that scientists at the atom-smashing Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Switzerland had observed the Higgs Boson.

The so-called God Particle is incredibly important because it is the particle that gives all other particles their mass and is therefore integral to the Standard Model of physics that defines our understanding of the physical world.

The Higgs Boson was theorised by Peter Higgs and François Englert in 1964, but it took the US$10 billion construction of the Large Hadron Collider and countless experiments decades later to prove the theory right.

The two scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize for physics in 2013 and thousands of researchers around the world are now building on the Higgs breakthrough to try to understand the dark matter and dark energy that makes up 95% of the universe and which doesn’t fit into the Standard Model.

As the Higgs Boson news was breaking in 2012, the National Ignition Facility’s future was looking grim. Its experiments had failed to deliver that crucial energy gain, despite several billion dollars of investment.

The Obama administration was about to cut its budget. But the facility survived, the scientists changed their approach and aided by advancements in laser technology, finally, a decade later, achieved the breakthrough they were seeking for so long.

Unintended spinoffs

This is Big Science at work, expensive projects that run for decades, and need the joint input of experts all over the world. Governments get little thanks from the public for funding them. But they’re essential to bringing about fundamental advances for humanity. They can also produce unintended spinoffs.

The World Wide Web was born at CERN when Tim Berners Lee developed a system allowing researchers to more easily share information across the facility’s computer network. It’s basically how we use the internet today.

The breakthrough at Livermore is genuinely significant, but scientists have many major hurdles to overcome before nuclear fusion reactors are supplying the electricity grid.

The experiments employed the biggest laser in the world, which uses a lot of energy to convert electricity into light. Big technical barriers have to be overcome for this to be suitable for energy production.

“The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory could in principle produce this sort of result about once a day – a fusion power plant would need to do it 10 times per second,” University of Oxford physics professor Justin Wark told the UK Science Media Centre.

“However, the important takeaway point is that the basic science is now clearly well understood, and this should spur further investment,” he said.

“It is encouraging to see that the private sector is starting to wake up to the possibilities, although still long-term, of these important emerging technologies.”

Competitive tension

Fusion for energy generation may finally actually be 30 years away, and hopefully much sooner if governments are willing to combine their resources to try and scale up what the Americans have achieved.

So, it won’t answer our more pressing need to lower greenhouse gas emissions dramatically in the next 20 years.

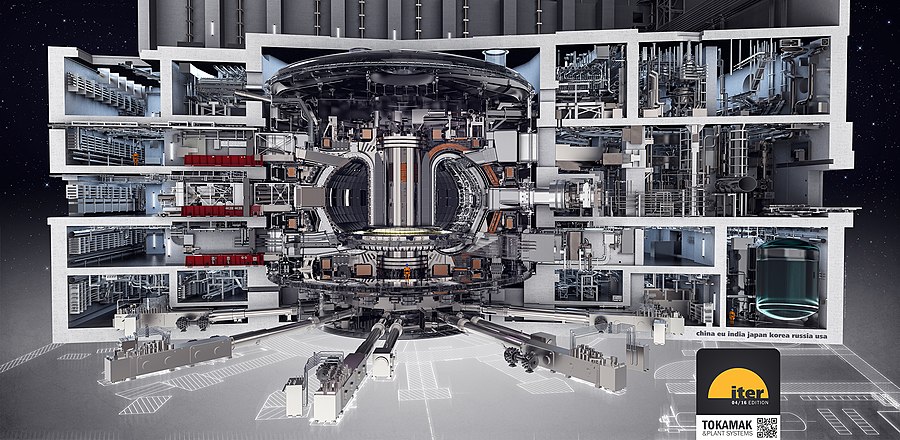

The success in the lab will, however, focus the minds of the team behind ITER, the US$20b International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor that is being built in France with the same clean energy goal in mind.

ITER uses a different technology, employing magnetic fields to compress a plasma and create a high-energy reaction. But fusion reactors employing this approach haven’t yet achieved energy gain. The US is a major funder of ITER too, but the competitive tension between the projects will be useful in speeding progress on fusion this decade.

The lesson from Livermore this week is that fundamental science is still crucially important and worth pursuing.

We’ve seen the results of it on a smaller scale in our own sustained scientific efforts in animal genetics and breeding and our world-class natural hazards research.

New Zealand is too small to invest heavily in Big Science projects, but our researchers are involved with the Large Hadron Collider and run experiments on synchrotron particle accelerators around the world.

We opted to reduce our national investment in another project, the Square Kilometre Array, a radio telescope tasked with improving our understanding of the universe’s origins.

The government decided, rightly in my opinion, that it wasn’t a priority for us.

Getting our priorities right

That’s why the setting of national research priorities, which the government proposes to finally have in place from 2024, is so important.

We need to identify where we can add value and what investment of taxpayer dollars and the efforts of researchers is going to pay off for the country. But we also need to fund basic science to a greater degree.

Australia is only now starting to reap the gains of decades of investment in quantum computing and quantum science, with around 20 startups now working in the field there.

The country now has a genuine edge in aspects of quantum useful to communications, sensing, encryption and high-capacity computing.

“We don’t know precisely how it will play out and over what timeframe,” Australia’s chief scientist, Dr Cathy Foley, said at a physics congress in Adelaide this week.

“We can’t say for sure which areas will see progress that surpasses expectations, and where it will fall short. Discovery is a rich and unpredictable process!

“As leaders in this field, we need to keep reinforcing that message, so investors and decision-makers understand that not every avenue will emerge in the sun. We do have to play the patience game.”

The scientists in Livermore have played that game ably and the eventual payoff could be huge for all of us.

Originally published on BusinessDesk.